| Singapore–Kuala Lumpur High-Speed Rail | |

| — | |

| Type | High-Speed Rail |

| Station Count | 8 |

| Line length | ~350 km |

| Termini | Kuala Lumpur (Bandar Malaysia) Singapore (Jurong East) |

| Depots | Serdang, Muar, Pontian |

| Operational Data | |

| Operators | – |

| Rolling stock | – |

| Electrification | – |

| Track gauge | Standard Gauge (1435mm) |

| Status | Project Terminated |

The Singapore–Kuala Lumpur High-Speed Rail is a cancelled high-speed rail project linking Singapore and Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. The service had intended to offer 90-minute travel times between the two cities.

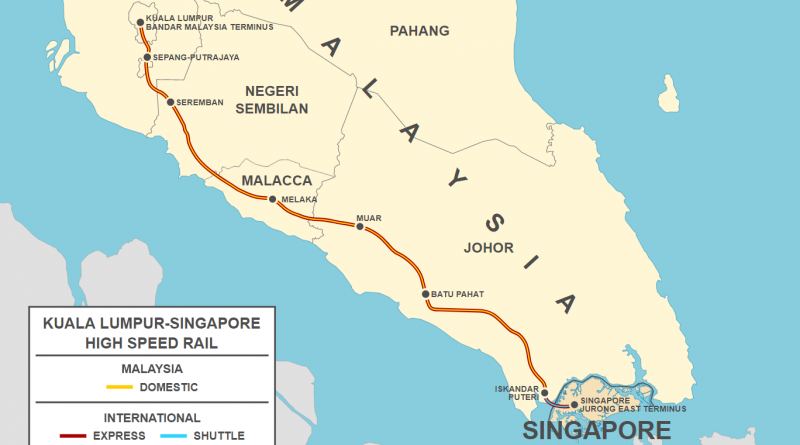

First announced in 2013, the 350-kilometre line would follow the west coast of Peninsula Malaysia with 8 stations at Kuala Lumpur, Putrajaya, Seremban, Ayer Keroh, Muar, Batu Pahat, Iskandar Puteri and Singapore. International services would operate from Kuala Lumpur, Iskandar Puteri and Singapore, with co-located customs facilities at these three stations. International passengers would clear customs of both countries at their point of departure.

The Singapore terminus of the route would be at Jurong East, at the site of the former Jurong Country Club. The Kuala Lumpur terminus would be at Bandar Malaysia. The line would have crossed the Strait of Johor via a 25-metre high bridge near the Second Link, and a tunnel portal and siding facilities would have been built at the site of the former Raffles Country Club.

When completed, the line would have cut travel time between Singapore and Kuala Lumpur to 90 minutes, compared with more than four hours by car and about five hours end-to-end by air (inclusive of check-in, baggage retrieval, etc.). Originally, construction was expected to begin in 2017 and projected to open in 2026, but project delays have pushed back both dates to May 2020 and January 2031 instead, and thereafter cancelled.

Timeline & History

- 2010: High-Speed Rail between Singapore and Kuala Lumpur highlighted

- 2013 (19 Feb): Singapore and Malaysia agreed to HSR project

- 2015 (Feb): Jurong East confirmed as Singapore terminus

- 2015 (9 Oct): Singapore and Malaysia jointly launch a request for information

- 2016 (19 Jul): Signing of Memorandum of Understanding (MOU)

- 2016 (13 Dec): Signing of legally-binding Bilateral Agreement

- 2016 (Dec) to 2017 (Jan): Jurong Country Club, Raffles Country Club acquired

- 2017 (16 Feb): Consortium awarded joint development partner contract to manage project

- 2017: Commencement of engineering studies and tenders

- 2018 (28 May): Malaysia’s newly-elected government under Tun Dr Mahathir announces ‘a final decision’ to drop the HSR, citing a project cost of RM110 billion (S$36.2 billion) and will not earn it a single cent

- 2018 (11 Jun): Backtracking on earlier comments, Tun Dr Mahathir says the project was temporarily shelved due to high costs

- 2018 (05 Sep): Formal postponement of HSR construction work announced, up to May 31, 2020. Revised opening target of Jan 1, 2031. Malaysia would reimburse Singapore $15 million by end-January 2019 for abortive costs incurred by the deferment, and both sides called off the ongoing international joint tender for the assets company.

- 2019 (28 Jun): Award of Technical Advisory Consultant (TAC) and Commercial Advisory Consultant (CAC) to Minconsult Sdn Bhd and Ernst & Young as the TAC and CAC respectively by MyHSR

- 2020 (31 May): Projected start of construction

- 2020 (31 May): Deferment of the Kuala Lumpur-Singapore High-Speed Rail project to 31 December 2020 at Malaysia’s request

- 2021 (1 Jan): Project formally terminated; with both countries failing to reach an agreement on changes proposed by Malaysia by the deadline of Dec 31

- 2031 (Jan 01): Targeted commencement of operations

- 2021 (Mar): Payment of SGD102,815,576.00 (RM320,270,519.24) has been made by the Government of Malaysia to reimburse the Government of the Republic of Singapore for costs incurred for the development of the HSR Project, and in relation to the extension of suspension of the HSR Project.

In 2010, as part of the Government of Malaysia’s Economic Transformation Programme (ETP) plans, the Southern Corridor High-Speed Rail (HSR) highlighted with the aim of improving the economic dynamism and liveability of Kuala Lumpur. Feasibility and conceptual studies soon followed.

On 19 February 2013 at a Leader’s Retreat, the Singapore and Malaysia Prime Ministers formally agreed to build the HSR. This was followed by the planning phase where the groundwork was laid for the fulfilment of the project. In Singapore, Jurong East was confirmed as the line terminus. The line will run underground, surfacing at Tuas and crossing the Strait of Johor via a 25-metre high bridge near the Second Link.

On 19 July 2016, both Governments signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) to develop the HSR with a targeted operational date of 31 December 2026. By formalising the line’s technical and security details as well as its regulatory, financing and procurement frameworks, among other things, the agreement paves the way for both sides to move from the planning phase to implementation. The HSR is expected to cost Singapore more than S$17 billion, and around 110 billion ringgit for Malaysia.

A legally-binding Bilateral Agreement was signed on 13 December 2016, paving the way for engineering studies and construction work. Between December 2016 to January 2017, land occupied by Jurong Country Club and Raffles Country Club was acquired by the Government for HSR construction. On 16 February 2017, a three-party consortium (made up of WSP Engineering Malaysia, Mott MacDonald Malaysia and Ernst & Young Advisory Services) won the joint development partner (JDP) contract, providing project management support, technical advice on HSR systems and operations, developing safety standards, and help with the preparation of tender documents for the LTA-MyHSR joint project team. Later that month, British architecture firm Farrells won the tender to develop the Singapore terminus.

On 28 May 2018, newly-elected Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad announced the cancellation of the HSR project, acting on promises to reduce the country’s debt. He cited the project’s high costs and negligible benefits to the country. However, he adopted a different stance in June 2018, commenting that the project was merely postponed until Malaysia was in more favourable financial conditions and would seek a deferment from Singapore. Amidst concerns of wasted expenditure, Khaw Boon Wan revealed in a parliament reply on 9 July 2018 that Singapore had spent “more than $250 million” to implement the HSR project up to the end of May 2018, which included costs for consultancies to design the civil infrastructure, costs for manpower and costs for land acquisition, with another $40-50 million more by the end of 2018.

Following bilateral meetings in August 2018, it was announced on 5 September 2018 that construction of the HSR project would be postponed until May 2020, with Malaysia reimbursing Singapore S$15 million (remitted on 31 January 2019) for abortive costs incurred by the deferment. Both countries also called off the ongoing international joint tender for an assets company to operate the 350km line due to the suspension, and HSR express services were then expected to commence on Jan 1, 2031, four years later than initially announced.

Media Leaks

On 25 November 2020, Malaysian news outlet Free Malaysia Today (FMT) reported that the HSR expected to resume without Singapore’s participation. Citing unnamed sources, the new plan was for the line to end in Johor Bahru, and that Putrajaya has informed its Singapore counterpart of the change in plans. It cited the sum of $250 million that Singapore would seek as the price to drop the deal. In return, a statement by Singapore’s Ministry of Transport reiterated that both countries are held to the legally-binding Bilateral Agreement, wherein Malaysia will bear the agreed costs incurred by Singapore in fulfilling the HSR Bilateral Agreement if the project was aborted by them.

On 13 December 2020, Malaysian news outlet The Malaysian Insight reported that Malaysia was prepared to pay Singapore RM300 million (S$99 million) in compensation, doubling down on initial reports that Malaysia intended to build the HSR without Singapore’s participation. The decision to not continue working with Singapore on the project was allegedly reached by the Malaysian Cabinet ‘last Friday’ (11 Dec 2020). A compensation sum of $104.67 million was to be paid to Singapore by 31 December, less than half of the $250 million sum quoted by the Free Malaysia Today article from November 2020. In addition, a medium-speed rail system was being considered to reduce project costs, albeit travelling slower than the 350 km/h top speed originally envisioned.

It was reported that Malaysia had asked to build a HSR station at the Kuala Lumpur International Airport, which Singapore had rejected, with the source claiming that the Republic perceived this as a threat to its aviation industry. The source also said that if Malaysia were to complete the HSR on its own, the project would cost around RM65 billion (S$21.4 billion), excluding the trains. Malaysia’s Ministry of Transport declined to comment, and Singapore’s Ministry of Transport said that further details would be announced in due course.

Formal termination

The Kuala Lumpur-Singapore High-Speed Rail (HSR) project was officially terminated on 1 January 2021, after both countries failed to reach an agreement on changes proposed by Malaysia by the deadline of 31 December 2020.

The Malaysian Government had proposed several changes to the HSR project in light of the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the Malaysian economy. However, an agreement was not reached in spite of discussions, and the HSR Agreement had lapsed on 31 December 2020. As a result, both countries will abide by their respective obligations, and will now proceed with the necessary actions, resulting from the termination of the HSR Agreement.

In a separate statement from Singapore’s Ministry of Transport, it said that Malaysia had allowed the HSR bilateral agreement to be terminated and has to compensate Singapore for costs already incurred, in accordance with the agreement. It added that both countries remain committed to maintaining good bilateral relations and cooperate closely in various fields, including strengthening the connectivity between the two countries.

Reactions to termination

Beyond the non-specific reasons for ‘failing to reach an agreement’ between both countries, several alternative sources have offered reasons for the cancellation, such as disagreements involving the realignment of the line to serve Kuala Lumpur International Airport initially reported in December 2020.

Former Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak, who was instrumental in Malaysia’s signing of a bilateral agreement with Singapore on the project in 2016, expressed disapproval at the cancellation. In a Facebook post on 1 Jan 2021, he said that building the HSR was justified as the benefits from an increase in tourists from Singapore would bring billions in revenue as well as create jobs for the people that will last for a long time. Najib also claimed that terminating the HSR in Johor Bahru was projected to cost around RM63-65 billion – which is not much different from the original cost estimate of RM60-68 billion for the original project terminating in Singapore.

In addition, the realignment of the line to Johor Bahru would also decrease projected ridership from 8.4 million a year to 4.2 million, which would significantly affect the economical feasibility of the line and potentially operate at a financial loss. This is exacerbated by the loss of commuters to and from Singapore, who could afford to pay more expensive fares for the service. Downgrading the HSR to a medium-speed rail would also lose its time-saving edge to commercial flights between Singapore and Kuala Lumpur.

Speaking to Free Malaysia Today for a 2 Jan 2021 article, veteran consultant Goh Bok Yen and Malaysian International Chamber of Commerce and Industry (MICCI) executive director Shaun Cheah said a rail project which does not directly connect Singapore to Malaysia would be “pointless”. Without Singapore in the picture, the proposed KL-JB rail line would just be a second domestic line which not only duplicates the Keretapi Tanah Melayu Berhad (KTMB) line between the two states but also competes with existing highway links and air transport. Goh said that it would be more prudent to skip a new rail line altogether and use the money, estimated to be in the billions, to improve KTMB’s capacity, widen roads, and put in place better public transport facilities.

Economic reasons were also highlighted by multiple parties in support of the original HSR proposal. The Kuala Lumpur-Singapore air route is among the busiest in the world owing to close business links between both countries, because Malaysia is an extension for many businesses headquartered in Singapore. The Republic attracts foreign direct investment and regional offices of multinational corporations because of the ease of doing business, political stability, and clarity of policies. In turn, Malaysia benefits as businesses expand operationally there, due to lower costs.

Compensation

A joint statement on the Settlement of Compensation Between the Government of the Republic of Singapore and the Government of Malaysia for the Kuala Lumpur – Singapore High Speed Rail (HSR) Project was issued on 29 March 2021, which announced that the payment of SGD102,815,576.00 (RM320,270,519.24) has been made by the Government of Malaysia to reimburse the Government of the Republic of Singapore. This is for costs incurred for the development of the HSR Project, and in relation to the extension of suspension of the HSR Project.

The two countries reached an amicable agreement on the amount following a verification process by the Government of Malaysia. This amount represents a full and final settlement in relation to the termination of the Bilateral Agreement.

Technology

Several countries like Japan and China were eyeing a slice of the lucrative contract and hoping to gain influence in the region. Both Japan and China have been aggressively promoting their domestic HSR technology, with Japan banking on its safety and reliability record, and China on its wealth of experience in rolling out the HSR domestically in a cost-effective manner. Other countries who have expressed interest include Korea and France, both of which also have domestic HSR networks.

Train Stations

- Bandar Malaysia (Kuala Lumpur)

- Sepang-Putrajaya

- Seremban

- Ayer Keroh

- Muar

- Batu Pahat

- Iskandar Puteri

- Singapore

External Links & References:

- Kuala Lumpur – Singapore High Speed Rail: Project Overview – MyHSR (PDF)

- PMs agree on high speed rail linking KL, Singapore – Straits Times

- KL, Singapore sign deal for high-speed rail; service slated to start by Dec 31, 2026 – Straits Times

- Singapore-KL high-speed rail deadline ‘ambitious but achievable’ – Straits Times

- Raffles Country Club to be acquired by July 31, 2018 to make way for S’pore-KL high-speed rail, Cross Island Line’s western depot – Straits Times

- 3-party consortium awarded joint development partner contract for Singapore-KL high-speed rail project – Straits Times

- Malaysia and Singapore agree to put HSR on hold, delay and costs to be discussed: source – The Business Times

- Malaysia, Singapore ink agreement to defer high-speed rail project for 2 years; KL to pay S$15m for suspending work – Straits Times

- MyHSR Corporation Proceeds with the Kuala Lumpur –Singapore High Speed Rail Project Review Exercise, Expects Completion by Year End – MyHSR

- Discussions on the Resumption of the Kuala Lumpur-Singapore High Speed Rail Project (KL-SG HSR) – Ministry of International Trade and Industry, Malaysia

- High Speed Rail project to go on without Singapore? | Free Malaysia Today (Accessed 25 Nov 2020)

- Response to media queries on KL-Singapore HSR (mot.gov.sg) (Accessed 26 Nov 2020)

- Malaysia to fly solo, pay off Singapore in HSR deal | The Malaysian Insight (Accessed 13 Dec 2020)

- Singapore, Malaysia in talks over High-Speed Rail project as deadline approaches, SE Asia News & Top Stories – The Straits Times (Accessed 14 Dec 2020)

- Response to media queries on KL-Singapore HSR (mot.gov.sg) (Accessed 14 Dec 2020)

- KL-Singapore High Speed Rail terminated after both countries fail to reach agreement on M’sia’s proposed changes, Politics News & Top Stories – The Straits Times (Accessed 1 Jan 2021)

- Termination of the Kuala Lumpur – Singapore High Speed Rail Project (mot.gov.sg) (Accessed 1 Jan 2021)

- Najib Razak – Posts | Facebook (Accessed 2 Jan 2021)

- Without Singapore, HSR is dead in the water, say experts | Free Malaysia Today (Accessed 2 Jan 2021)

- Joint Statement on the Settlement of Compensation Between the Government of the Republic of Singapore and the Government of Malaysia for the Kuala Lumpur – Singapore High Speed Rail (HSR) Project – Ministry of Transport (Accessed 29 Mar 2021)